|

Search the site:

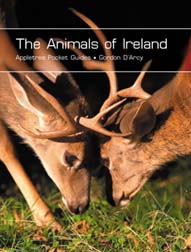

This selection of Irish animals, native or introduced, is taken from the Appletree Press title Animals of Ireland. There will be a number of extracts from the book in coming months. The book contains highly detailed full colour illustrations to complement the detailed explanatory text.

[This article is taken from the Appletree Press title Animals of Ireland.

Background - Animals of IrelandMany of the animals that are now found in lreland in a wild state are descendants of the first waves of north-westerly spreading fauna - from before the first arrival of humankind in Ireland. Others are the progeny of creatures introduced accidentally or intentionally by man over the past nine millennia.Before Ireland became insular in form (a thousand or so years before the coming of man), it was part of the land mass of present-day Europe. Unfathomable quantities of water having been solidified in the form of glaciers, Ice Age animals roamed freely over the dry land. Fossils indicate that Reindeer, Lemmings, Lynx, Giant Irish deer and before that even Mammoths roamed the tundra on what is now Ireland. With the advent of warmer conditions following the end of the Ice Age, the Mammoth and the Giant deer became extinct. The others which were not able to survive in the temperate conditions retired northwards with the retreating Arctic circle. By the time man settled in Ireland these Arctic species were long gone but he found a post-glacial environment densely populated with a varied indigenous fauna. The land was thickly wooded with pine, hazel and birch and contained Wolves, Brown bear, and Wild boar. Other more familiar creatures like Red deer, Foxes, Badgers, Stoats, Pine martens and Otters were undoubtedly in Ireland from this time too. But a range of mammals including Moles, Voles and a number of amphibians and reptiles did not get there before low-lying tracts of land were engulfed by the rising sea level - a product of the melting ice. Although the land surface itself recovered to a height many feet higher than it had been under the weight of the ice, it never again provided the means whereby animals from Europe could gain access to Ireland overland. Some of the first settlers must have brought animals with them but being primarily hunter/gatherers they favoured a nomadic-style life, roaming the land and leaving behind only isolated signs of their effect on it. It was not until some 3,000 years had elapsed that the first farmers found their way to Ireland. The bogs were swelling imperceptibly out of the vegetation-clogged wetlands and the landscape was a rich green canopy of hardwood trees like oak, ash and elm. These early agriculturalists made clearings in the forest and set up semi-permanent enclosures to protect their livestock from wild animals - particularly wolves. They husbanded primitive cattle, goats, sheep, pigs and eventually horses, and made an abiding impact on their terrain. Extensive grazing had been created for stock prior to the advent of Christianity. Though much still remained as wilderness, a network of monastic settlements was established throughout the land from which early Irishmen cultivated the countryside. The colourful poetry and other writings of these Christian Celts not only indicate the wide variety of animals that cohabited the country then, but also speak of the empathy which existed between these people and their wildlife. The Normans, who were hunting enthusiasts, maintained wild habitats and introduced the Rabbit and the Fallow deer for this purpose. Inadvertent introductions from this period included the House mouse and the Black rat. The latter (now almost non-existent in Ireland) was once abundant and carried the infamous plague, or 'Black Death', in its fleas. This disease decimated the population of Ireland in the 14th century. The larger, more robust and more resilient Brown rat has since displaced its black relative and, though notorious for its capacity to spread disease, is generally regarded as being less harmful. Up until the Middle Ages landscape modification by man had been occurring to fluctuating degrees, though undoubtedly less significantly than in Britain and elsewhere in Europe. Retarded technological development and relatively low population tended to render these changes impermanent, permitting wildlife to survive both in abundance and in diversity. As a consequence of the Tudor and subsequent plantations, however, dramatic changes occurred which resulted in the virtual total eradication of Ireland's woodlands by 1800. Other once wild habitats like bogs, fens and mountains have since been utterly manmodified as well. Countless small, now-obscure creatures must have gone as a result of these changes - now lost to Ireland's native ecology. Gone too are the Bear, the Wolf, the Wild boar, the Red squirrel (since reintroduced) and almost exterminated were the Pine marten and the Red deer. It is perhaps only through adaptation that some of these more 'habitat specific' animals managed to survive at all. Despite the fact that some animals were brought to Ireland by man and others were exterminated by him, more than half the number considered here are thought to be native - long-term survivors. These include the Lizard, the Newt, the Bats and a number of the larger mammals. A few - the Stoat, the Otter and the native Hare - are regarded as Irish endemics (i.e. races unique to Ireland) and there were probably others. These species can be (due to factors like colour difference, size, etc.) readily distinguished from their British or European counterparts. The Irish Stoat for instance is smaller and darker than the animal from Britain, having evolved in separation. The Irish Otter is still common and widespread in suitable habitat, in contrast to the decline which had been recorded throughout Britain and Europe. Recent research into Ireland's seven Bat species has shown them to be more widespread and locally common than was formerly thought. The European stronghold for the Leisler's and the Daubenton's bats may be in Ireland and this country has thus a special responsibility for their continued survival and that of the Lesser horseshoe bat, which also has a particularly western distribution. An entire group of animals - the cetacea (Porpoises, Dolphins, Whales) - are less well known than their terrestrial relatives. In fact, until relatively recently it was not known that many species from the smallest, the Porpoise, to the largest, the Blue whale, passed close to Ireland's western Atlantic seaboard on their seasonal migrations. During the course of commercial whaling activities, carried out in the early years of the 20th century off Ireland's western coast, half a dozen of the larger species were sadly exploited, including the Blue, Fin, Humpback, Sei, Right and Sperm whales. Thankfully these activities were wound up before they were permanently destructive. Cetacea of many species are still to be seen off Irish coasts and the sightings of some, like Killer whales off Cape Clear Island, have shown that these leviathans are still regular visitors to Irish inshore waters.

|

Animals of Ireland, fully illustrated in colour.

[ Back to Top ]

All Material © 1999-2009 Irelandseye.com and contributors