|

|

|||

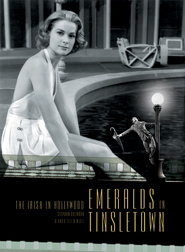

This Chapter is from Emeralds in Tinseltown: The Irish in Hollywood, written by Steve Brennan and Bernadette O'Neill, and published by Appletree Press

The Abbey Theatre - Lost and Found in HollywoodIt has been said that Fitzgerald’s characterisations on screen have rarely been surpassed. His understanding of film was immense and he often transformed mundane scenes into magic moments. Such was the case in Two Years Before the Mast in which he played a ship’s cook.In one scene he is called upon to serve food to his bellicose captain who complains about the meal. Fitzgerald’s character is called on to reply in a most insubordinate tone. They ran through the scene several times, but something just wasn’t working. On the next take, instead of sticking with the scripted lines, Fitzgerald remained silent. He picked up the food, sniffed at it. Disdain was written on Fitzgerald’s face and silent mutiny in his eyes. The scene was a take – it was brilliant. The Hollywood party circuit may not have been his passion but he soon found other things to amuse him in his new life. ‘Perhaps his most revealing hobby is cutting records of those radio advertising jingles,’ observed a piece in Collier’s (magazine). ‘He plays these home-made records over and over, chuckling with glee at the inanities of the music and rhymes. He is making a collection of such pieces to send to Ireland to be played on the phonograph in a certain pub so that some of his old pals may enjoy this new American art form.’ It all seemed so many worlds away from the nine-to-five job as a Dublin civil servant that he held down until well into his middle years, while moonlighting at the Abbey as an actor with his brother Arthur Shields, who was equally lauded by Hollywood. Born in Dublin by the name of Joseph Shields on March 10th 1888, Barry Fitzgerald was recruited into the mundane world of government clerking upon finishing school and remained there until he was forty-one. Hardly the stuff from which Hollywood legends are made, but then very little about Barry Fitzgerald and his younger actor brother Arthur fitted any mould. Fitzgerald, who came across his stage name through a print error on an early Abbey Players’ bill, was ten years older than Arthur. The pair were inseparable as boys growing up in Dublin. The Shields family was involved with a local amateur drama group, The Kincora Players, with which the brothers got their first stage experience. But the first step to the professional footlights was taken by younger Arthur. The security of the civil service in those economically depressed and politically uncertain days kept the elder brother entrenched in his day job. Arthur was working at Dublin publishing firm Maunsels, while going to acting classes at the Abbey Theatre in the evening. He eventually took up employment with the Abbey on a full time basis at a salary of £1 per week, a decent wage back in 1914. Barry followed Arthur to the Abbey. The Abbey was a creative cradle for names that would be literary giants, William Butler Yeats, John Millington Synge, Padraig Colum, Sean O’Casey. Initially, Barry played walk-on parts to fill in the crowd scenes. Eventually he began to accept bigger parts. “But because he didn’t want his supervisor at the day job to know what he was up to he asked the company to bill him as Barry Fitzpatrick. A printer got it wrong and the name Barry Fitzgerald appeared on the program,” recalled Dublin journalist Jack Jones, a nephew of the brothers. For seventeen years Fitzgerald led this double life until he was forced to make a decision. The Abbey was touring to London with The Silver Tassie, a play by a major new Irish writer, Sean O’Casey, and Fitzgerald held a leading role. Finally, but not without weighing all the pros and cons, this shining light of a great theatre resigned his clerking job. But the brothers’ lives had not been confined to the theatre in those days of turmoil in Ireland. Arthur could thank the Abbey for indirectly landing him in the thick of the Easter Rising of 1916. Arthur was a volunteer in the Irish Citizen Army and had been issued with a handgun, Jones recounted: ‘In a fit of confused logic that he never could fully explain he decided that the best place to hide the revolver that was issued to him was beneath the stage of the Abbey,’ Jones would recall. ‘When the call to arms came he rushed to the theatre and had the dickens of a time trying to get to his gun so that when he reached the meeting place for his particular group of volunteers they had already departed.’ An officer immediately ordered the young actor into a company of volunteers that was headed for the General Post Office in the heart of Dublin. This was to be the scene of the fiercest fighting and the place from which one of the leaders of the Rising, Padraig Pearse, would proclaim to a staggered populace that Ireland, under force of arms was now a Free State. Eighteen-year-old Shields was in the thick of it. ‘I got off a few shots through a window but to the best of my knowledge I never hit anybody,’ he confided to his nephew years later. Shields was rounded up with most of his fellow volunteers and interned in a prison camp in Wales until a general truce was called in 1922. “The important people were still kept in jail. The unimportant people like myself were let loose,” he informed an American journalist in later life. But for now it was back to the Abbey – and to more battles.

|

[ Back to top ]

All Material © 1999-2009 Irelandseye.com and contributors