|

|

|||

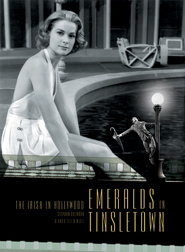

This Chapter is from Emeralds in Tinseltown: The Irish in Hollywood, written by Steve Brennan and Bernadette O'Neill, and published by Appletree Press

The Abbey Theatre - Lost and Found in HollywoodAs Hollywood sought more and more reality and authenticity in the 1940s, the movie moguls stepped up the worldwide search for a new breed of acting talent that could bring to the screen renowned theatrical backgrounds. Broadway was mined – but so too were the great theatres of the world. To Hollywood came a new generation of Irish actor, a generation spawned of the country’s first national theatre, the famed Abbey Players. It is one of the great inconsistencies of Irish history that the Irish – with their distinctive temperament, flair for self-expression and poetry – had no real tradition of drama. Yet Ireland has produced more writers and performers for its size than any other nation. The growth of Irish drama was stunted with the demise of the Old Gaelic Order, but with a resurgence of nationalist spirit, poetry, literature and theatre in the twilight years of the nineteenth century a new dramatic energy was born. This extraordinary artistic meld of art and nationalism was sowing the seeds for an infant Irish native theatre, The Abbey Theatre. Providing the great energy behind the renaissance were such literary and stage luminaries as W.B. Yeats, Lady Gregory, Sara Allgood, and J.M. Synge, the poet and playwright.“We have a popular imagination that is fiery, magnificent and tender, so that those who wish to write start with a chance that is not given to writers in places where the spring-time of local life has been forgotten and the harvest is a memory only and the straw has been turned into bricks.”The fruit of this renaissance was plucked by Hollywood. And those who came from that illustrious Abbey stage to colonise the film town were easily the strangest misfits that Tinseltown has ever seen. The gnome-like Irishman shuffled out of the laundry shop into the pounding summer heat of Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood to continue his quest. The battered tweed suit and cap that he was wearing would have been more appropriate for a chill Irish winter than the heat-wave that was choking him in Los Angeles. The man was none other than Barry Fitzgerald, and he was on a quest for his clothes. He’d left them into some dry cleaning establishment or other on the Sunset strip and had completely forgotten which one. Fitzgerald, the loveable little genius from Dublin’s famed Abbey Theatre, the rogue priest from Going My Way, one of the biggest box office hits of 1944 (which co-starred Irish-American Bing Crosby) was spending his day wandering in and out of dry cleaning shops in the somewhat confusing new world he had found himself, far from his beloved native Dublin. The world and Hollywood had fallen in love with the diminutive actor and he was all at sea. Being a Hollywood movie star was new to him and so was Hollywood. ‘He finds it all rather bewildering,’ Fred Stanley wrote in the New York Times in 1945 of Fitzgerald’s transplant from the boards of the Abbey to fame in Hollywood. ‘He resents the disruption of his previously inconspicuous private life. He can’t even browse in Los Angeles bookshops or join in a discussion with strangers at some out-of-the-way bar-room or drug store without being targeted as Father Fitzgibbon. His old clothes and cloth cap, which once kept him inconspicuous, now make him a marked man.’ Barry Fitzgerald, perhaps the most unlikely Irish star that Hollywood ever was home to, went on to win an Academy Award for the role of wily old twinkle-eyed Father Fitzgibbon, who made life a conundrum of frustration for the parish curate played by Crosby. His comment on winning the coveted honour was typical of the reluctant Hollywood recruit. “Although it’s nice to know I’m getting along all right in my work… a man of my age likes as much peace and quiet as possible. If I have to go through another one of those things they’ll probably discover me in Forest Lawn Cemetery.” Fitzgerald, who was fifty-six years old then, simply could not fathom what was happening to him. He was besieged by fan mail he had no idea what to do with, and was so engulfed by well-wishers and admirers calling to his home off Hollywood Boulevard that he regularly took flight. One of his favourite ports of refuge was the Hollywood home of another Irish expatriate, May Flo Gogarty, sister of the renowned Irish poet, author,politician and surgeon Oliver St John Gogarty. ‘Hollywood just baffled Barry,’ May Flo’s daughter, the late Hollywood agent Maureen Oliver recalled once. ‘He would come to our home and sit alone playing the piano for hours. But if anybody entered the room he would stop playing because he was too shy to continue.’ Oliver laughed as she remembered the displaced Abbey actor arriving at her mother’s home ‘in a terrible state and moaning, “I’ve lost all my clothes.” He had taken them to a laundry but for the life of him he could not remember which one. We searched Hollywood for hours looking for his clothes, his entire wardrobe, but we never did find them. We had to lend him a suit that we dug up somewhere for him to wear to the studio because he did not have a stitch left but the old things he was standing up in. And that was at the time when he was making $75,000 a picture (then a top Hollywood salary range).’ The laundry lapse was probably not too surprising considering that the new Hollywood star, described by Tinseltown columnist Hedda Hopper as ‘a gnome-like little man with shaggy eyebrows that defy gravity, training or barber shop cajolery’ was gaining a reputation as by far the worst-dressed celebrity in the movie industry, whose stars in the day were pictures of sartorial elegance. He appears to have favoured tweeds (unpressed) and cloth caps. But what may have been an amusing if eccentric dress sense to some was clearly an offence in some high society quarters as Fitzgerald would discover to his amusement. A great golfing enthusiast, Fitzgerald became a regular at a prestigious Santa Barbara club of which Avery Brundidge, former head of the Olympic Games Council, was president. Brundidge was sitting in the clubhouse one afternoon gazing out at the course when he spied an odd little figure in what he considered to be an appalling state of dress shuffling about. It was Fitzgerald. The offender was ordered off the course and out of the club by Brundidge, who didn’t realise the shabby intruder was one of the biggest Hollywood celebrities of the day. On another occasion the actor was invited to play tennis with Charles Chaplin. To be invited to Chaplin’s lavish mansion was considered an ‘A-list’ invite. Unaware or uncaring of the social importance of an invitation to Chaplin’s for tennis, Fitzgerald appeared, much to his host’s chagrin, in a shaggy old sweater, shoes stained with motor oil from his motorcycle, and faded, yellowy pants. Chaplin, decked out in gleaming whites, trounced Fitzgerald in straight sets. The two stars remained friends, but Fitzgerald was never invited to tennis at Chaplin’s again. For all of that, Hollywood loved the eccentric Irishman who in turn was fast assimilating into his new life. ‘In Hollywood these days everyone it seems is excited about Barry Fitzgerald… (he) is in greater demand by the studios than any character has ever been in the history of cinema,’ exclaimed the usually conservative New York Times. It has been said that Fitzgerald’s characterisations on screen have rarely been surpassed. His understanding of film was immense and he often transformed mundane scenes into magic moments. Such was the case in Two Years Before the Mast in which he played a ship’s cook. In one scene he is called upon to serve food to his bellicose captain who complains about the meal. Fitzgerald’s character is called on to reply in a most insubordinate tone. They ran through the scene several times, but something just wasn’t working. On the next take, instead of sticking with the scripted lines, Fitzgerald remained silent. He picked up the food, sniffed at it. Disdain was written on Fitzgerald’s face and silent mutiny in his eyes. The scene was a take – it was brilliant. The Hollywood party circuit may not have been his passion but he soon found other things to amuse him in his new life. ‘Perhaps his most revealing hobby is cutting records of those radio advertising jingles,’ observed a piece in Collier’s (magazine). ‘He plays these home-made records over and over, chuckling with glee at the inanities of the music and rhymes. He is making a collection of such pieces to send to Ireland to be played on the phonograph in a certain pub so that some of his old pals may enjoy this new American art form.’ It all seemed so many worlds away from the nine-to-five job as a Dublin civil servant that he held down until well into his middle years, while moonlighting at the Abbey as an actor with his brother Arthur Shields, who was equally lauded by Hollywood. Born in Dublin by the name of Joseph Shields on March 10th 1888, Barry Fitzgerald was recruited into the mundane world of government clerking upon finishing school and remained there until he was forty-one. Hardly the stuff from which Hollywood legends are made, but then very little about Barry Fitzgerald and his younger actor brother Arthur fitted any mould. Fitzgerald, who came across his stage name through a print error on an early Abbey Players’ bill, was ten years older than Arthur. The pair were inseparable as boys growing up in Dublin. The Shields family was involved with a local amateur drama group, The Kincora Players, with which the brothers got their first stage experience. But the first step to the professional footlights was taken by younger Arthur. The security of the civil service in those economically depressed and politically uncertain days kept the elder brother entrenched in his day job. Arthur was working at Dublin publishing firm Maunsels, while going to acting classes at the Abbey Theatre in the evening. He eventually took up employment with the Abbey on a full time basis at a salary of £1 per week, a decent wage back in 1914. Barry followed Arthur to the Abbey. The Abbey was a creative cradle for names that would be literary giants, William Butler Yeats, John Millington Synge, Padraig Colum, Sean O’Casey. Initially, Barry played walk-on parts to fill in the crowd scenes. Eventually he began to accept bigger parts. “But because he didn’t want his supervisor at the day job to know what he was up to he asked the company to bill him as Barry Fitzpatrick. A printer got it wrong and the name Barry Fitzgerald appeared on the program,” recalled Dublin journalist Jack Jones, a nephew of the brothers. For seventeen years Fitzgerald led this double life until he was forced to make a decision. The Abbey was touring to London with The Silver Tassie, a play by a major new Irish writer, Sean O’Casey, and Fitzgerald held a leading role. Finally, but not without weighing all the pros and cons, this shining light of a great theatre resigned his clerking job. But the brothers’ lives had not been confined to the theatre in those days of turmoil in Ireland. Arthur could thank the Abbey for indirectly landing him in the thick of the Easter Rising of 1916. Arthur was a volunteer in the Irish Citizen Army and had been issued with a handgun, Jones recounted: ‘In a fit of confused logic that he never could fully explain he decided that the best place to hide the revolver that was issued to him was beneath the stage of the Abbey,’ Jones would recall. ‘When the call to arms came he rushed to the theatre and had the dickens of a time trying to get to his gun so that when he reached the meeting place for his particular group of volunteers they had already departed.’ An officer immediately ordered the young actor into a company of volunteers that was headed for the General Post Office in the heart of Dublin. This was to be the scene of the fiercest fighting and the place from which one of the leaders of the Rising, Padraig Pearse, would proclaim to a staggered populace that Ireland, under force of arms was now a Free State. Eighteen-year-old Shields was in the thick of it. ‘I got off a few shots through a window but to the best of my knowledge I never hit anybody,’ he confided to his nephew years later. Shields was rounded up with most of his fellow volunteers and interned in a prison camp in Wales until a general truce was called in 1922. “The important people were still kept in jail. The unimportant people like myself were let loose,” he informed an American journalist in later life. But for now it was back to the Abbey – and to more battles. The renaissance of Irish drama that the Shields brothers were embroiled in had kicked up a fiery young playwright out from the cracks of the cobblestones of Dublin. His name was Sean O’Casey. And Irish audiences were none too happy with how this working class writer saw them. “I remember the time we put on The Plough and the Stars (by O’Casey) in 1926. The second-night audience threw things so steadily it was almost worth your life to go out on the stage. We acted around the missiles for two acts but in the third act the barrage got too heavy for us and we finally ran the curtain down,” Shields recounted of those tempestuous days. “W.B. Yeats made a magnificent speech, telling the audience that they were disgracing themselves in the eyes of the world…” But even if one fiercely conservative element of Irish society was disgracing itself with violent outbursts at such unthinkable contentions as the existence of prostitutes and sex out of wedlock in Ireland, being put about by the Abbey Players, the world of theatre beyond Ireland didn’t seem to care. This valiant troupe of actors, writers, poets, artists and dreamers had wrenched a new style of theatre from a long sleeping spirit, a minimalist method of acting that stressed mood, expression and form as much as it did the golden dialogue of its writers. By the 1920s the Abbey Players were being invited to tour around the world, which is how the brothers first came to America. Whistle-stop tours of the United States became a regular feature for the Abbey Players. Shields delighted in telling of one stop in Portland, Oregon, when the company was so anxious to catch a train to the next venue that the scenery was thrown eight stories from a window to the snow-covered ground to save time. “The audience was requested to remain in the theatre to avoid falling objects,” the actor recounted. But the brothers’ first American screen appearance would not come until 1936 when the Irish-American director John Ford brought them from Ireland to make his screen version of O’Casey’s The Plough and the Stars. “The reward was six weeks at $750 a week – more money than we in Ireland believed the mints produced,” Barry Fitzgerald remembered. “I intended going on from there to the South Seas and around the world. But just as I was oiling up the bicycle and packing the other shirt, Mary Pickford put me under a one-year contract – and never used me. I have been in Hollywood ever since.” Following his year of inactivity under contract to Pickford, the work began to flow in for Fitzgerald. Irish-American director Leo McCarey cast him in the role of the parish priest in Going My Way. He had seen Fitzgerald years earlier when the Abbey had visited Broadway with Paul Vincent Carroll’s classic The White Steed. McCarey had been so impressed with the actor’s work that he had “filed me away for future reference”. This was the beginning of a peculiar relationship between the eccentric actor and Hollywood, in which Fitzgerald carved out for himself an island of privacy, surrounded himself with mementos of Dublin and held an open house for any acquaintance from home, or acquaintance of an acquaintance, that would call. He shunned the town’s high society parties, dressed and spoke pretty much as he pleased, while remaining one of the industry’s highest paid and sought-after actors for many years. Arthur was not so quick to settle, but in 1944, more because of precarious health and the need to live in a warm climate, Arthur set up permanent residence a few blocks from his brother in Hollywood with his wife Aideen O’Connor, also of the Abbey. The film town embraced the brothers. Their most recognised film was of course John Ford’s Irish romantic ditty The Quiet Man, with John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara. Fitzgerald played the roguish matchmaker while Shields was the wily Protestant clergyman. The brothers also appeared together in Ford’s Long Voyage Home. Other Hollywood roles for Shields included Drums Along the Mohawk with Henry Fonda and Claudette Colbert, and Lady Godiva with Maureen O’Hara. But others from the Abbey would not find Hollywood so generous a host. The legendary Sara Allgood was a case in point. ‘Sara Allgood was a great – a very great – stage actress, who managed to transform many poor feature films in which she appeared into works of art,’ wrote one of the most respected film historians of our day, Anthony Slide of this Abbey luminary, whom Hollywood tormented into an abyss of despair. Allgood, known to her friends as Sally, was born in Dublin on October 31st 1893 into a family that might have been considered ‘comfortable’ in those days. Her father provided for his eight children through his job as a proofreader with a publishing firm. She was educated at the Marlborough Street Training College in Dublin, which she left at the age of fourteen full of dreams of becoming an actress like her idol Sarah Bernhardt. It would have been a heady dream for a working-class girl in the Dublin of the day, were it not for the existence of a small amateur drama group called the National Theatre Society that was staging works drawn from Irish history. The Society was later to merge with W.B. Yeats and Lady Gregory’s Irish Literary Theatre to become The Abbey. The acclaimed Irish poet Padraig Colum would vividly remember his first sight of the teenage Allgood in her first role with the Society in Yeats’s The King’s Threshold. “I recall one evening when some young men and women, all with office or workshop employments, gathered in a small hall in a side street in Dublin to make a third attempt to gain an audience of a few hundred for plays dealing with Irish life and tradition. Benches had been put together, a platform had been built, and amateurs… were assembled for a rehearsal of a new play by William Butler Yeats,” the poet told. ‘Who is the new girl?’ someone asked referring to Allgood. “The new recruit had dark hair parted in the centre and a face that somehow had a doll-like contour,” Colum recollected. “Suddenly she had taken on an extraordinary dignity. The voice was resonant; it had a deep and moving quality. And the girl was making something significant of what she had to do. I saw Yeats turn to W.G. Fay (a key founding member of the Abbey and that play’s director) (and say), ‘Fay, you have an actress there.’ ” Allgood would become one of the great Abbey actors, hailed by theatre critics world-wide for her creations of some of the immortal characters that would be born of O’Casey, Yeats and Synge, most notably the title role of Juno, the poverty-stricken but proud wife and mother in O’Casey’s classic work of tenement life in Dublin, Juno and the Paycock. She would later reprise the role on screen under the direction of Alfred Hitchcock in a British production that would pave the way for Allgood’s call to Hollywood and to a way of life for which she was utterly unprepared. By now an internationally recognised actress, a veteran of the London and Broadway stages and with several British films to her credit, including Hitchcock’s Blackmail, Allgood was summoned to Hollywood for the pivotal role as mother to Lady Emma Hamilton in the classic That Hamilton Woman. This “earnest” person, as the poet Padraig Colum had described her, an actress who held her art above all, came to a Hollywood that in 1939 was perhaps at its most capricious, and deserving of its new moniker ‘Tinseltown’. A new word had entered the lingo; that word, as Allgood would learn to her eternal regret, was ‘bankability’. Allgood could never come to terms with the fact that her talent would now take second place to her drawing power at the box office when it came to the casting process. For a moment fickle Hollywood had the welcome mat out for the Abbey actress, and briefly she had her hour in the arclight. ‘The delay in Miss Allgood’s arrival in American film is strange,’ piped the New York Herald Tribune following the release of That Hamilton Woman in 1941. ‘Consider these facts. She has an international reputation on the stage. Hollywood has never had enough good actresses of her type, and Miss Allgood for years has been interested in doing film.’ Her most singular triumph came with a major role later that same year in John Ford’s screen adaptation of How Green Was My Valley co-starring Barry Fitzgerald and a rising Irish screen star Maureen O’Hara. Allgood was nominated for an Oscar for her work in the film which garnered no fewer than six Academy Awards that year. Then something happened that is simply inexplicable. Hollywood shut the door in Allgood’s face. Despite her monumental talent, glowing praise from the critics and an Oscar nomination, the offers of good roles for the now middle-aged actress dwindled to a trickle. “Sally went to Hollywood with high hopes. Being the great artist that she was it was a great shock to her, to say the least, to be treated in a high-handed manner,” the actress’s niece, Mrs Pauline Page, confided to Anthony Slide, one-time director of the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences. “I’ll never forget one thing she said to me when I was in her beautiful Spanish home in Beverly Hills. She hadn’t been getting much work and Mr Bernie (Allgood’s agent) was urging her to give a big party and invite important people to it. Sally was dreadfully depressed and later said to me, ‘I could never do a thing like that. I could never prostitute my art.’ Another thing she said to me, ‘When you go back to your home and your family, you can think of me sitting alone… afraid to go out for fear I should miss a call to work.’ ” Allgood did play some small parts in a number of movies, usually for 20th Century Fox, after that but the characters were mostly clichéd Irish maids or old Irish mothers, roles which never allowed her to display her true worth on screen. Her final role in Hollywood came in Cheaper By The Dozen (1950), a 20th Century Fox production. “The salary is cut to the bone, but no matter, it’s activity, and that’s the main thing,” Allgood wrote to a friend, Gabrielle Fallon, in Dublin. It would be her last letter home. A heart attack took her that same year as she ‘waited for the phone to ring’ in Hollywood. ‘For those who saw her even once on the screen or on the actual stage, the announcement of the death of Sara Allgood is bound to leave a deep sense of loss,’ lamented Padraig Colum. If Allgood had become a victim of that all too common affliction that continues to bedevil the industry today – a dearth of strong roles for mature actresses – her male colleagues from the Abbey had no such torments. The brothers Fitzgerald and Shields were working in major roles regularly, as was another member of the Gaelic sanctum, Dudley Digges, during the 1940s. Though Digges, also a founding member of the Abbey, landed in Hollywood as a mature, reluctant visitor of fifty-one years, he went on to star and feature in more than fifty movies, including the 1930 version of Mutiny on the Bounty and a 1931 production of The Maltese Falcon. Born in Dublin in 1879, Digges got his first training at the Abbey which he joined in 1901 and where he and Allgood formed a lifelong friendship. Barry Fitzgerald revered Digges whom he credited for encouraging him to take those first walk-on roles at the Abbey so many years before. Digges was one of the first of the Abbey troupe to emigrate to the U.S. when he joined the Manhattan Theatre and later became a central figure in the formation of the famous New York Theatre Guild in 1919. Appearing in more than 3,500 performances with the Guild, Digges was a lauded Broadway actor, praised for his dynamic stage presence and remarkable voice, a gift that Hollywood craved most when the talkies arrived in the late 1920s. To its horror, the movie industry discovered that the voices of many famous silent-screen names were completely unsuitable for the talking pictures. Hollywood careers were crashing left and right as swashbuckling actors squeaked lines in high-pitched nasal tones and beautiful sirens muttered indistinct words in heavily accented European or Bronx accents. When the call went out to from Hollywood for ‘actors who could speak lines,’ Digges was among the first recruits. But the instant fame that Digges achieved in the Hollywood of the Thirties and Forties with its glitzy premieres, industry parties and carefully managed hierarchical system did not sit easily with this balding, somewhat rotund and mature stage thespian. He joined his fellow Abbey veterans nightly in homely get-togethers, mostly at Fitzgerald’s house, and surrounded himself with books, mostly Irish classics. A constant disappointment to journalists seeking headlines, Digges told one writer, “I’m really a dull fellow. I’ve managed to get through life without important or exciting incident. What I have to show I show upon the stage. I don’t have adventures and I don’t make headlines.” But he did make movies, great movies, with such milestones as The General Dies at Dawn (1936), Valiant is the Word for Carrie (1936), and Raffles (1940) among his myriad credits. ‘Ireland is his first love, the stage his second,’ The New York Times wrote of Digges in 1944, so it was perhaps fitting that his final role came not in Hollywood but on Broadway in the original production of the Eugene O’Neill classic The Iceman Cometh, in which he created the role of the saloon keeper. One evening during the run of the play he confided in a friend, “Do you know that this play gives me about forty-three years in the New York Theatre?” He never mentioned Hollywood. “I’ve just been sitting here thinking how lucky I have been to keep with good things and good people.” He died of a stroke just a few months after the final curtain of the production following a long bout of failing health. He was sixty-eight. An obituary in the Daily News said simply, ‘He delighted American audiences for forty-three years with his stage and screen characterisations.’ If Digges felt out-of-step in Hollywood in his day there was one place in the film town he could always call home, and that was Barry Fitzgerald’s house. A centre of hospitality for many a friend from the old days in Dublin, Fitzgerald and Shields lived most of their later lives in California. While Barry stayed on in Hollywood, Arthur set up home in Santa Barbara, California, which he festooned with pictures of Dublin, old Abbey posters and playbills. The brothers remained inseparable in their self-imposed exile, but parted ways when it came to leisure activities. Barry was a motorcycle fiend and loved nothing more than gunning his Harley Davidson through the Hollywood Hills with an Iroquois Native American pal, Gus Tallon. Arthur, on the other hand, preferred the more leisurely pursuit of stamp collecting. Common to both was their love of old friends and they continued for many years to provide open house for many others from home who would wander through the film town. One such was a fiendishly handsome young actor from Cork, Kieron O’Annrachain, known to the world of international theatre and film by this time as Kieron Moore, Playing the dark-eyed bully Pony Sugrue, he gave Sean Connery almost as good as he got in that Walt Disney celebration of Ireland of the shamrocks, Darby O’Gill and the Little People with Jimmy O’Dea playing the king of the Leprechauns. Moore, another who first trod the boards professionally at the Abbey, was born in Skibbereen in County Cork, the son of a fiercely nationalistic Gaelic-speaking family. It was an inheritance that burned deep. “Even today, although I think in English now, I say my prayers in Irish,” Moore would confess to Walt Disney publicist Joe Reddy many years later when he called Hollywood his home in the 1950s. It was Moore’s passion for the Gaelic language that led him to the Abbey Theatre when he was still in his teens. He wrote, produced and acted in an Irish language play that went on in a small theatre in Dublin just around the corner from the Abbey. The production closed within the week and Moore and his backers were out of pocket to the tune of £30, a vast sum in a city where a working man brought home £2 a week, if he was lucky. In a desperate, almost naïve attempt to recoup the enormous loss for his backers, Moore, who was then just seventeen years old, fired off a letter to the Irish Taoiseach Eamon De Valera, explaining the predicament. De Valera, a voice in the movement to restore the Gaelic language, sent Moore a personal cheque for £30 by return mail. Subsequently he was summoned in to see Frank Dermody, director of the Abbey. “The message I got was to come in and audition for a secondary role in an Irish language production. It was the first time I met Frank Dermody (a powerful figure in Irish theatre), and I was terrified.” Moore was cast in leading role in the production. “I was good, but not fantastically so,” Moore remembered of that career-defining moment. The role led to the offer of a full-time job at the Abbey, with Moore playing lead roles and bit parts (“there was no star system at the Abbey,” Moore explained) in a variety of productions from William Butler Yeats’s Kathleen Ni Houlihan to The Lost Leader, a Gaelic version of Tristan and Isolde, and The Rugged Path in which Robert Clark, head of Associated British Picture Corporation spotted him. A summons to a screen test in London followed – and that’s when the trouble began. Moore threw some clothes in an old suitcase and was off to London. The British film company was so impressed by Moore’s presence in the film test that he was offered a seven-year contract. The excited seventeen-year-old sent word home to Ireland of the great news and received by return a flat ‘permission refused’ dispatch from his father. Still legally a minor, Moore could not sign that passport to the silver screen without his father’s consent. Bitterly disappointed but now utterly consumed with determination to pursue his acting career, he doggedly planted himself in London. He scraped by with work in repertory theatre and managed to get some film work. His performance in a production of Sean O’Casey’s Red Roses For Me earned him a contract with Alexander Korda’s film company. This time there was no parental veto barring his way and Moore was no longer the gangly youth who had left Dublin with a dream and a cardboard suitcase. He was a swarthy, tall, confident leading man who knew his way around a film sound stage. ‘He has dark brown curly hair and large liquid eyes. Although his name and upbringing are as Irish as the shamrock, he could be mistaken for a Spaniard, an Italian, a Frenchman or a South American,’ one enamoured journalist wrote of him. His reputation grew on the British screen, with such films as Anna Karenina in which he co-starred with Vivien Leigh, and A Man About The House in which he played an Italian. Moore quickly drew the attention of Hollywood. Roles in American films incuded 20th Century Fox’s David and Bathsheba and Columbia’s Ten Tall Men, and of course Walt Disney’s Darby O’Gill and the Little People. Though Moore was feted by the studios and had regular encounters with Hollywood, he never settled down in the film town, preferring to commute from his home in England, much in the same way as a bevy of other former Abbey actors whom Hollywood briefly courted. Among these of course is Jackie McGowran, the rubber-faced genius who was the embodiment of the Beckett actor on stage and who showcased his talent for comedy and off-the-wall characters in such films as Darby O’Gill and the Little People and the Warner Brothers-Seven Arts Release Two Times Two with Gene Wilder and Donald Sutherland. More substantial films included Doctor Zhivago and Lord Jim. He also appeared in Ford’s Irish movies Young Cassidy and The Quiet Man. Another fleeting Abbey visitor to Hollywood was Denis O’Dea, who was married to fellow Abbey luminary Siobhan McKenna. O’Dea played mostly character roles in the Hollywood productions in which he appeared and his credits include The Informer, Odd Man Out, The Mark of Cain and the role of Doctor Livesey in the RKO-Walt Disney Technicolor version of Treasure Island. The story of the Abbey players in Hollywood and their diverse experiences with the siren would not be complete without mention of Una O’Connor. The Abbey graduate, born Agnes Teresa McGlade in Belfast in 1880, had made her mark on the London and New York stages before arriving in the film town in 1924 to recreate for the screen her stage role as the housekeeper in Noel Coward’s Cavalcade for Fox Films. O’Connor was to prove no less an enigma in Hollywood than any of her fellow Abbey players. A curious biography put out by RKO Studios in 1946 would say of her, ‘When she went (from Hollywood) to New York in 1945 to do a stage play, she lost her apartment and since has lived at a hotel in Santa Monica. She drives a car back and forth to the studio. She is a teetotaler and never serves alcohol at any of the informal gatherings at her home. The friends she assembles at her home don’t play cards either but spend their time in the discussion of art, books, and topics of the day… Steak and kidney pie is one of Miss O’Connor’s favourite dishes. She cannot swim, but bathes in the ocean and loves to lie on the sand and let the breakers toss her about. She has a keen sense of humour, is reserved, but friendly if someone else takes the first advances; likes to have her fortune told with tea leaves; is never lonely as long as she can be outdoors in beautiful scenery or has a good book, believes that gremlin is a modern name for the Irish “little people”. ’ O’Connor, who died in New York in 1959 aged seventy-eight, included among her credits such films as Random Harvest, The Plough and the Stars, Lloyds of London, This Land is Mine, The Sea Hawk and The Bells of St Mary’s. She also appeared in numerous films by horror genre director James Whale including The Invisible Man and Bride of Frankenstein. J.M. Kerrigan was another former Abbey actor to whom Hollywood beckoned. First appearing in Ford’s The Informer playing the Dublin joxer who befriends Victor McLaglen’s Gypo Nolan after he’s been paid for informing on his best friend, Kerrigan settled in Hollywood permanently in 1935. Kerrigan was assigned mostly character roles, including parts in numerous John Ford films. He also appeared in Gone With The Wind. The Abbey Theatre clearly was a breeding ground for a diverse group of passionate actors who would come to Hollywood, some to stay and thrive, some to pine and wilt. But all of them, in their own way, left an indelible imprint in the town’s legendary history.

|

[ Back to top ]

All Material © 1999-2009 Irelandseye.com and contributors