|

|

|||

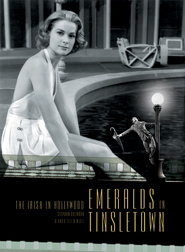

This Chapter is from Emeralds in Tinseltown: The Irish in Hollywood, written by Steve Brennan and Bernadette O'Neill, and published by Appletree Press

The Irishman, the Mermaid and the FoxThe Hollywood Career of Herbert Brenon - part 2 of 4When Brenon brought the picture in nine months later, the mogul made his move. He ordered that Brenon’s name be struck off the film’s credits. It was a devastating blow to the young director who saw A Daughter of the Gods as the crowning achievement of his career. He decided to fight back and took the only course open to him. He sued. Nobody in Hollywood, not even Brenon himself, believed he could successfully challenge the power of William Fox. But he was ready to try. It was a costly battle for Brenon and predictably one he did not win. But the case marked a milestone in the film industry, and thereafter all directors insisted on clauses in their contracts that ensured their work could not be attributed to another director that an irate studio might bring in, or credit on the movie as punishment for failing to toe the company line. A Daughter of the Gods became another box office record with Brenon’s trademark island maidens and shimmering tropical vistas. As for the inflated budget that Brenon left behind? In as brazen a stunt that Hollywood had ever witnessed Fox billed Brenon’s unaccredited epic in screaming headlines as ‘the first million-dollar’ moving picture ever made. And Brenon? The battle that might have been the end of a short but illustrious career became just one of many legends in an Irish immigrant’s triumphant life in Hollywood. Brenon was born in Dun Laoghaire (then called Kingstown). When his father, a writer, was appointed theatre critic of a London newspaper, young Brenon was transplanted out of quiet Kingstown into the hurly-burly metropolitan world of London theatre. The boy was agog as he trawled the West End theatre circuit with his father, experiencing the excitement of opening nights, giggling at the antics of his father’s theatre friends, hanging on their ribald thespian tales spun amid the heady atmosphere of cocktails and green rooms. The footlights, the boy decided, were his life’s beacons. When his father moved the family to New York a few years later, sixteen-year-old Brenon haunted Broadway. He worked as an office boy in a theatrical agency by day and moonlighted as a stage extra by night. There was nothing he wouldn’t or couldn’t do to be part of this world of wonder they called Vaudeville. He was a stage manager, a messenger, an actor, a lighting assistant, a director. The boy was becoming a showman. A trip to the sticks of Minneapolis in 1904 to direct a vaudeville circuit show changed his life. A pretty actress, Helen Oberg, was the beauty of the theatre company and Brenon fell for her at first sight. They married and hit the vaudeville circuit as a team, billing themselves Herbert Brenon and Helen Dowling. Their act was a hit. The vaudeville circuit was their home for the next few years until Brenon began to notice that audiences were beginning to thin out. At the same time, the moving picture nickelodeon houses were booming. The death knell was sounding for vaudeville and Brenon heard it loud and clear. He had just turned thirty, he was a husband and recently a father. He was a top of the bill name on vaudeville when he took a job as a lowly paid story editor with Carl Laemmle’s Independent Motion Picture Company and set about making a complete nuisance of himself. He wasn’t shy about showing off his years of training and deep understanding of theatre, and would even suggest camera setups and stage timing of shots, much to the annoyance of the established directors at the company. But Laemmle decided to give this loudmouth story editor a shot at directing his own picture; Brenon delivered a finely honed one-reeler called All For Her, a romantic ditty that audiences seemed to like. It was enough to earn Brenon a full-time directing job and for the next year he was a whirlwind of creativity, often directing two or three shorts a week for IMP. But the unmitigated vaudeville showman in him could not be suppressed and increasingly he began to step from behind the camera to do dangerous stunts that his actors baulked at. This penchant for doubling as stuntman in his own movies became his trademark, even at the height of his fame, and on more than one occasion it nearly killed him.

|

[ Back to top ]

All Material © 1999-2009 Irelandseye.com and contributors