|

|

|||

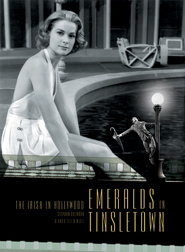

This Chapter is from Emeralds in Tinseltown: The Irish in Hollywood, written by Steve Brennan and Bernadette O'Neill, and published by Appletree Press

The Irish Cowboys - part 1John Ford was filming Cheyenne Autumn out in the wind carved mountain spires and red, eroded landscape of Monument Valley along the Arizona-Utah state line and within the Navajo Indian Reservation. The ageing director was dining after a long day’s shoot with his cast, among them Patrick Wayne, son of John Wayne, one of Ford’s oldest and dearest friends, Ricardo Montalban, Dolores Del Rio, Carroll Baker and Jimmy O’Hara, younger brother of Maureen O’Hara, another treasured friend. It had been a magical evening out in a magical place with songs being sung by Navajo, Irish, American and Latin.“‘Sing the national anthem, Jimmy,” Ford said. It was getting late now. O’Hara knew what he meant… he sang ‘The Wearing of the Green,’ a song traditionally sung during Easter Week in Ireland. After the second refrain, Ford contributed a verse,’ remembered the director Peter Bogdanovich in a moving and very personal insight into his old friend published in Esquire magazine in 1964 under the heading, ‘The Autumn of John Ford’. Instead of the National Anthem, O’Hara gave Ford a rendition of ‘The Wearin’ of the Green’. The account serves wonderfully to express the dichotomy that was this Irishman and classic American, John Ford. (While Ford is perhaps most commonly associated with his wonder-ful Westerns, his early classic Stagecoach among them, he would repeatedly return to Irish themes, setting to film such works as his Oscar-winning adaptation of Liam O’Flaherty’s tragic drama The Informer starring Victor McLaglen; Sean O’Casey’s The Plough and the Stars and, of course, The Quiet Man, that Irish romp about a Yank (John Wayne) returning home to Ireland, falling in love with the local lass (Maureen O’Hara), fighting her brother (McLaglen) and encountering all sorts of mischief from a cast of rogues, Barry Fitzgerald, Arthur Shields and the impish Jackie McGowran among them. On the one hand, Ford seemed to be always in search of his Irish roots, while on the other he was singularly American, a Naval officer and perhaps the most important chronicler of the American saga on screen. His career and his life are signposted both by his efforts to explore his Irish heritage and by his monumental salutes to the land of his birth, the United States. He was born John Martin Feeney in Portland, Maine, in 1894, the son of an Irish immigrant saloonkeeper, Sean Feeney from Spiddal in County Galway. Ford’s mother Barbara was from the same county, but the couple didn’t meet until they arrived in their new home of Portland, Maine. Shortly after graduating from Portland High School in 1914 Ford, still using the family name of Feeney, “left the Irish neighbourhoods of this port city” to try his luck in Hollywood, where his older brother Francis was finding considerable success as an actor in the new movie business. He stepped off the train in downtown Los Angeles, lugged his bag onto a tram headed for Hollywood, paying a dime for the twelve-mile ride through the citrus groves that blossomed around the town. He was hoping that Francis would be there to meet him as planned, but he wasn’t too worried; things were going to work out well, he sensed. Francis’s letters home had been filled with colourful frontier yarns of the young film town and Feeney reckoned this was just the place for him. Francis, who had anglicised his last name to Ford for the movies, was indeed there to meet his younger brother when he stepped off the trolley at Sunset Boulevard. Across the dust road was the barn rented by Cecil B. DeMille where Squaw Man had been filmed just two years before. But the brothers were headed further afield to the studios of cowboy star Tom Mix, the ‘Mixville Studios’ in Edendale. With apologies Francis explained to the new arrival that without any experience under his belt there was not a lot for him to do in Hollywood. For the time being, young Sean would work as a stable hand at the studio. That was just fine with the young adventurer. It didn’t take him long to work his way up playing bit parts, including a hooded clansman in D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (the studios were constantly looking for extras to do crowd work). A later move to Universal and another menial job would ultimately propel him into the apprentice directing ranks. A publicity sheet put out in 1941 by 20th Century Fox says glibly, ‘Ford got ‘staggered’ after he was elevated from ‘prop’ boy at Universal Studios to the job of directing… In six years he had made two hundred Westerns – short and long ‘cliffhangers,’ all speedy. He had served his apprenticeship. He is still fast, perhaps faster than ever, but he is one of the most finished directors in Hollywood, and four times a winner of the Academy award for the best film of the year.’ The press release, typical of its day with a wordy and breathless style, describes Ford thus: ‘In person, Ford is a hulking, rugged, soft-stepping six-footer, hidden behind a flop hat, a large pipe, rubber-tyred spectacles and an up-turned collar. He wears the same hat, worn coat and scuffed shoes – an outfit that a junkman would thank you not to fling in his cart. But there is an aura of quality about them: the hat was especially made, the coat woven of Harris tweed, the shoes of Cordovan leather.’ During that ‘apprenticeship’ he had become a contract director responsible for numerous Westerns, many of them starring Harry Carey Sr, the legendary Irish-American Western star. Feeney, now calling himself John Ford in the style of his brother, was becoming a respected figure among the cowboys of Hollywood who rode for the movies. These were true cowhands who years earlier had been moving herds in Montana, Colorado or Wyoming before migrating to Hollywood in search of work. If a director could gain the respect of these tough men he would have their co-operation – without which it would be almost impossible to bring in a movie on schedule or on budget. Ford, who drank, fought and played poker with the toughest of the Hollywood posse, was high in their standing. His roustabout manner would remain a trademark of the director throughout his life. ‘I love Hollywood,’ he once said, ‘I don’t mean the higher echelons, I mean the lower echelons, and the grips, the technicians.’ It was the common touch of this tall, burly son of an Irish saloon keeper that probably contributed most to his ability to make gritty, truthful accounts of the West typified by such enduring films as Stagecoach, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon and, much later The Searchers. Stagecoach challenged Gone with the Wind (which won) and The Wizard of Oz for best picture in the Oscar race in 1939. It should be noted that many critics felt that because Stagecoach was shot in black and white at a time when colour had arrived, there was an unfairly negative vote. Ironically, Ford, the man who boasted, “I make Westerns,” won his first Oscar not for a Western but for his Irish movie The Informer made earlier in 1935. Two more Academy Awards for best direction came his way for his adaptation to screen of two great literary classics, The Grapes of Wrath and How Green Was My Valley in 1940 and 1941 respectively. Stagecoach would mark a milestone in cinema history in another way though. It marked the beginning of a close working relationship and friendship between John Wayne (who had distant family roots in Ulster) and Ford. They went on to make nine movies together, including of course The Quiet Man. It was said that Stagecoach in fact made Wayne’s career. ‘At the age of thirty-two after nearly ten years of making around eighty low-budget Westerns, the six-foot-four Wayne received new life when Ford cast him in the role of Ringo (in Stagecoach),’ writes Sam B. Girgus in his book Hollywood Renaissance.

|

[ Back to top ]

All Material © 1999-2009 Irelandseye.com and contributors